Only one nation in the world can celebrate the New Year or Hogmanay with such revelry and passion – the Scots!

It is believed that many of the traditional Hogmanay celebrations were originally brought to Scotland by the invading Vikings in the early 8th and 9th centuries. These Norsemen, or men from an even more northerly latitude than Scotland, paid particular attention to the arrival of the Winter Solstice or the shortest day, and fully intended to celebrate its passing with some serious partying.

In Shetland, where the Viking influence remains strongest, New Year is still called Yules, deriving from the Scandinavian word for the midwinter festival of Yule.

It may surprise many people to note that Christmas was not celebrated as a festival and virtually banned in Scotland for around 400 years, from the end of the 17th century to the 1950s. The reason for this dates back to the years of Protestant Reformation, when the straight-laced Kirk proclaimed Christmas as a Popish or Catholic feast, and as such needed banning.

And so it was, right up until the 1950s that many Scots worked over Christmas and celebrated their winter solstice holiday at New Year when family and friends would gather for a party and to exchange presents which came to be known as hogmanays.

There are several traditions and superstitions that should be taken care of before midnight on the 31st December: these include cleaning the house and taking out the ashes from the fire, there is also the requirement to clear all your debts before “the bells” sound midnight, the underlying message being to clear out the remains of the old year, have a clean break and welcome in a young, New Year on a happy note.

Immediately after midnight it is traditional to sing Robert Burns “Auld Lang Syne”. Burns published his version of this popular little ditty in 1788, although the tune was in print over 80 years before this.

“Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot and auld lang syne

For auld lang syne, my dear, for auld lang syne,

We’ll take a cup o kindness yet, for auld lang syne.”

An integral part of the Hogmanay party, which is continued with equal enthusiasm today, is to welcome friends and strangers with warm hospitality and of course lots of enforced kissing for all.

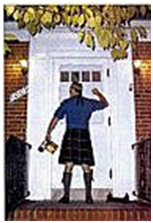

“First footing” (or the “first foot” in the house after midnight) is still common across Scotland. To ensure good luck for the house the first foot should be a dark-haired male, and he should bring with him symbolic pieces of coal, shortbread, salt, black bun and a wee dram of whisky. The dark-haired male bit is believed to be a throwback to the Viking days, when a big blonde stranger arriving on your door step with a big axe meant big trouble, and probably not a very happy New Year!

The firework displays and torchlight processions now enjoyed throughout many cities in Scotland are reminders of the ancient pagan parties from those Viking days of long ago.

The traditional New Year ceremony would involve people dressing up in the hides of cattle and running around the village whilst being hit by sticks. The festivities would also include the lighting of bonfires and tossing torches. Animal hide wrapped around sticks and ignited produced a smoke that was believed to be very effective in warding off evil spirits: this smoking stick was also known as a Hogmanay.

Many of these customs continue today, especially in the older communities of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. On the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, the young men and boys form themselves into opposing bands; the leader of each wears a sheep skin, while another member carries a sack. The bands move through the village from house to house reciting a Gaelic rhyme. The boys are given bannocks (fruit buns) for their sack before moving on to the next house.

One of the most spectacular fire ceremonies takes place in Stonehaven, south of Aberdeen on the north east coast. Giant fireballs are swung around on long metal poles each requiring many men to carry them as they are paraded up and down the High Street. Again the origin is believed to be linked to the Winter Solstice with the swinging fireballs signifying the power of the sun, purifying the world by consuming evil spirits.

For visitors to Scotland it is worth remembering that January 2nd is also a national holiday in Scotland, this extra day being barely enough time to recover from a week of intense revelry and merry-making. All of which helps to form part of Scotland’s cultural legacy of ancient customs and traditions that surround the pagan festival of Hogmanay.

by Ben Johnson

Ref: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-History-of-Hogmanay/