The Battle of Culloden – The 275th Anniversary 16 April 1746-2021

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields-Deployments

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields

The Battle of Culloden

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland.

Historical Background to the Battle

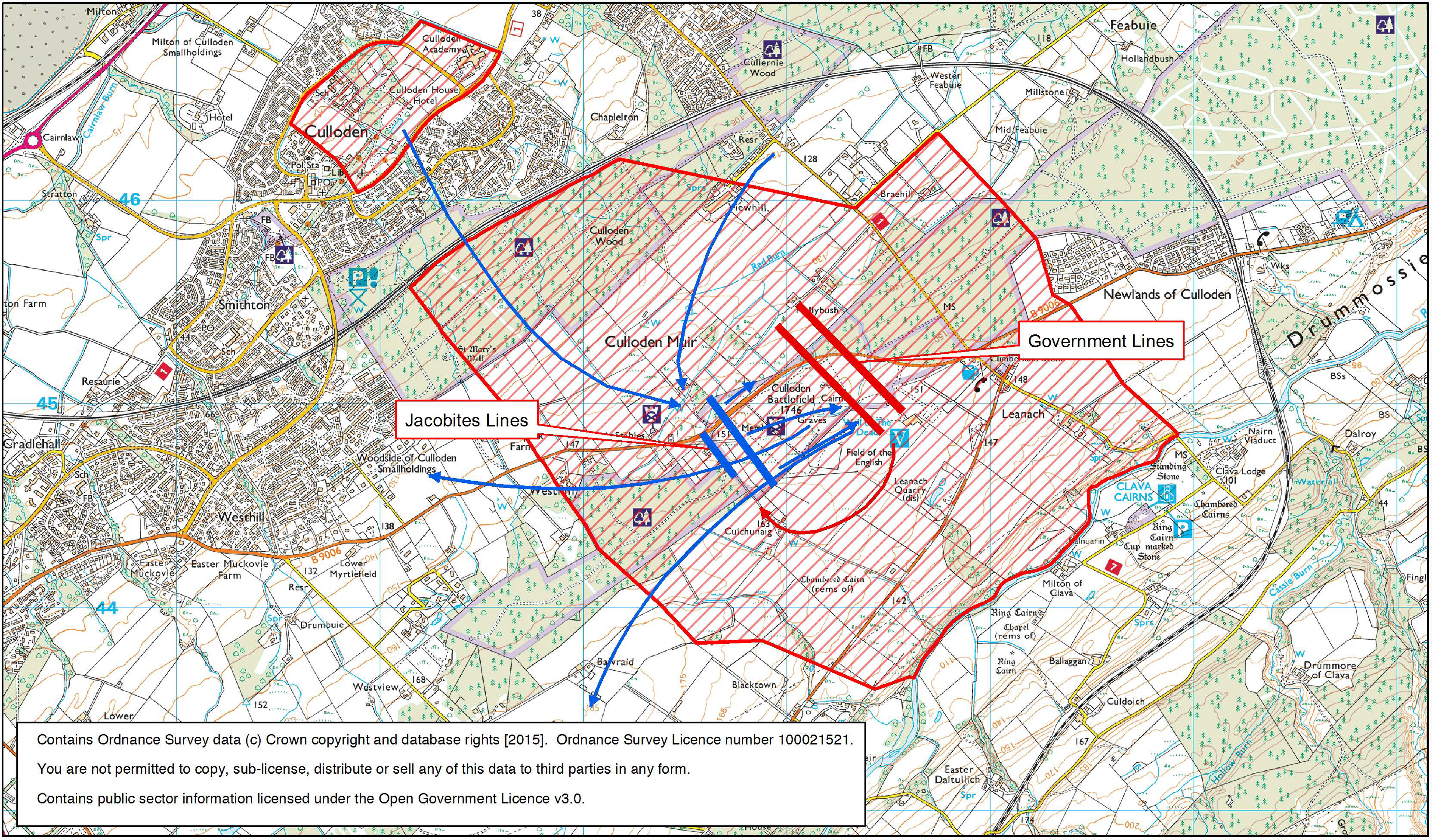

Overnight on 15 April 1746, the Jacobites marched to Nairn in an unsuccessful attempt to surprise the Government force in their camp, following which they were forced to march back towards Inverness with the Government army close behind. Early the following morning, on 16 April 1746, the Jacobite army under Charles Edward Stuart returned to Culloden and took up position on Drummossie Moor, between two stone enclosures at Culwhiniac on the south and Culloden Parks to the north.

The Government army formed up around 700m to the east, positioned at a slight angle to the Jacobite line. Seven battalions made up their front line, three ranks deep, with Barrell’s and Monro’s regiments positioned on the left. Twin batteries of 3 lb guns were located between each battalion. The second line was initially made up from five battalions, with three in reserve but, before battle commenced, two of these reserves (Pultney’s and Battereau’s) were pushed forward to the right flank of the first and second lines to prevent outflanking by the extended Jacobite left.

The battle opened with an exchange of artillery fire, during which the Government guns quickly took the upper hand over the Jacobite artillery. After suffering this galling fire for some time, the Jacobite infantry surged forward, beginning with the centre of the line made up from the men of Clan Chattan.

The right wing, including men from the Atholl Brigade, was a little slower off the mark, and this staggering of the advance created a diagonal movement, with boggy ground, a track running across the moor, gently sloping topography and heavy fire further directing the advance toward the left flank of the Government line. The MacDonalds and others on the left were the last to move forward.

They were not to make good progress as they were starting at a greater distance from the Government line than the centre and the right. Heavy fire from the Government artillery effectively stopped them in their tracks.

With the charge underway, the Government artillery changed from round shot to case and grapeshot and, when the Jacobites reached about 45m, the Government troops discharged a volley of musketry into the body of the charging enemy. The losses must have been terrible, but the momentum and determination of the charge was enough to carry the attackers crashing into the front of the Government left, between Barrell’s and Monro’s regiments.

Although they managed to hack their way into the front line, many Jacobites found themselves sandwiched between the muskets and bayonets of the front and second lines, and it is here that the Jacobite struggle effectively came to a bloody end. At this point, Wolfe’s and Ligonier’s regiments counter-attacked, moving from their position on the left of the second line around the left of the front line, from where they could deliver flanking fire into the mass of Jacobites engaged with Monro’s and Barrell’s regiments, the latter of which must have been close to breaking.

Meanwhile, the dragoons on the Government left, under General Hawley, made intelligent use of the terrain and moved behind the Jacobite right, after passing through breaches made by the Campbells in the enclosure walls to the south of the field. By this time, all was lost for the Jacobites and, under the protection of a covering action by their cavalry and the infantry detachments of the second line, Charles’ army streamed from the field. Having taken the day, the Government line advanced in close order, dispatching the wounded and those too slow to escape. The cruel aftermath of the battle has entered into the popular imagination and there are many stories of Jacobite wounded being dragged from their places of shelter and shot against walls, and of the barns in which they sheltered being burned to the ground after the doors had been bolted.

Events & Participants

Culloden is one of the most iconic battles in the history of the British Isles. It is of immense historical significance because it was both the final battle of the Jacobite Risings and the last pitched battle on the British mainland. Its importance resulted in many detailed contemporary records and maps, and has stimulated considerable subsequent research and archaeological investigation, making it the best understood battlefield in Scotland.

The battle brought an end to the series of Jacobite uprisings that had spanned a period of fifty-seven years. The immediate aftermath saw sustained oppression of the Highlands by the Government in an attempt to break down the clan system and marked a major change in the trajectory of British history.

In the longer term, the influx of Scottish troops, particularly Highlanders, into the British army was to make a major contribution to British success in Canada against the French in the Seven Years War, which broke out in 1756, and would continue to play major roles in subsequent conflicts.

The two best-known figures were undoubtedly the two opposing commanders. Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, was born in 1720 and was the grandson of the deposed King James VII & II. His father, James Frances Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, had made previous unsuccessful attempts to restore his line to the British throne, and Charlie, the Young Pretender, subsequently took up the cause. Landing at Glenfinnan on 19 August 1745, he embarked on an eight month campaign which initially met with some success, entering Edinburgh without resistance and then swiftly routing a Government force at Prestonpans, before advancing into England.

His army reached as far as Derby by December, but by this point the campagn was already beginning to unravel. The Jacobites withdrew to Scotland, and despite continued attempts to gain the upper hand, including a victory at Falkirk, they were slowly driven back into the Highlands and their final fate at Culloden. After the battle, Charlie was able to escape back to the continent, and would never again openly return to Britain, despite initial attempts to resurrect his cause. As the years passed he grew increasingly bitter about his defeat, before he finally died an overweight alcoholic in Rome in 1788.

The Government commander was Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and second son of King George II. Born on 15 April 1721, by the time of Culloden, he was an experienced soldier, having served in the Royal navy before transferring to the army in 1742, where he served overseas in Europe and the Middle East. He was serving in mainland Europe when the 1745 Rising began, and once the threat became clear with the Jacobite advance into England, he was recalled to take overall command of all forces in Britain. Cumberland arrived in Scotland in late January, determined to pursue and destroy the Jacobite army, and he took the opportunity when it arose at Culloden. In the aftermath of the battle, many of the crimes atrocities committed against the Jacobites and, subsequently, the wider Highland population, can be attributed to Cumberland. He was determined to end the Jacobites once and for all, by crushing their very way of life. His genocidal actions would earn him the nickname of Butcher Cumberland, and the atrocities committed after Culloden are the chief reason none of the British Army regiments who served there list it in their battle honours. Initially, Cumberland was held as a hero in England and much of Lowland Scotland, but his fame would not last, and his nickname of Butcher began to spread wider as the atrocities became clear. He was forced to resign from public office following a disastrous defeat at Hanover in 1757, and would die in London in 1765.

Lord George Murray was one of the senior commanders of the Jacobite army in the ’45 Rising. Born at Huntingtower Castle near Perth in 1694, at aged 18 he served with the British Army in Flanders. Murray and two of his brothers took part in the Jacobite Rising in 1715, after which he had to flee into exile in Europe. He returned and commanded part of the Jacobite forces at Glenshiel in 1719. Murray was wounded in the battle and again forced to escape to Europe after the Jacobite defeat. After being pardoned for his involvement in 1725, Murray returned to Scotland and in 1728 married Amelia Murray, heiress of Strowan. Murray initially refused to join the 1745 rising, but later sided with the Jacobites once more, being made a lieutenant-general by Charles. He commanded the left wing in the Jacobite victory at Prestonpans, but opposed the subsequent plan to advance into England. During the debate at Derby, Murray was a strong supporter of withdrawing to Scotland. Murray commanded the rearguard during the retreat, but Charles increasingly distrusted him. At Culloden, Murray unsuccessfully attempted to convince Charles of the unsuitability of the location for the Jacobite army. In the aftermath of the defeat Murray attempted to gather the remnants of the force at Ruthven Barracks, but with the failure of the Rising and Charles’ flight back to Europe Murray had no choice but to return into exile himself at the end of 1746. This third exile would be his last, and he never returned to Scotland before his death in 1760 in Holland.

James Wolfe was an officer in the British Army from 1741 until his death in 1759. He was serving on the continent as Captain in the 4th Regiment of Foot when it was among the forces recalled to Britain in 1745 to deal with the Jacobite Rising. He was present at the battle of Falkirk, after which he was promoted to serve as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Hawley, and Culloden, where in the aftermath it is said he refused a direct order from Cumberland himself to execute a wounded Jacobite. Although he served in many capacities in his career, including several postings within Scotland after Culloden, and was held in high regard for his abilities by many, remaining so today, his most famous accomplishment is undoubtedly the victory over the French at Quebec in 1759. As Major-General, he devised a plan to draw French forces out from the city and fight the British on ground which favoured Wolfe’s force. He led the assault himself on 13 September 1759, but was fatally wounded in the early stages of the battle, and Wolfe died shortly afterwards.

Also among the forces on both sides at Culloden were numerous clan chiefs, lords and notable figures. For the Jacobites these included Donald Cameron of Lochiel, Alexander MacGillivray, Charles Fraser of Inverallochie, James Drummond, Master of Strathallan, Donald MacDonell of Lochgarry and Lords Elcho and Kilmarnock. Present in the Government force were John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll, the Earl of Albemarle, William Anne and Lord George Sackville.

Battlefield Landscape

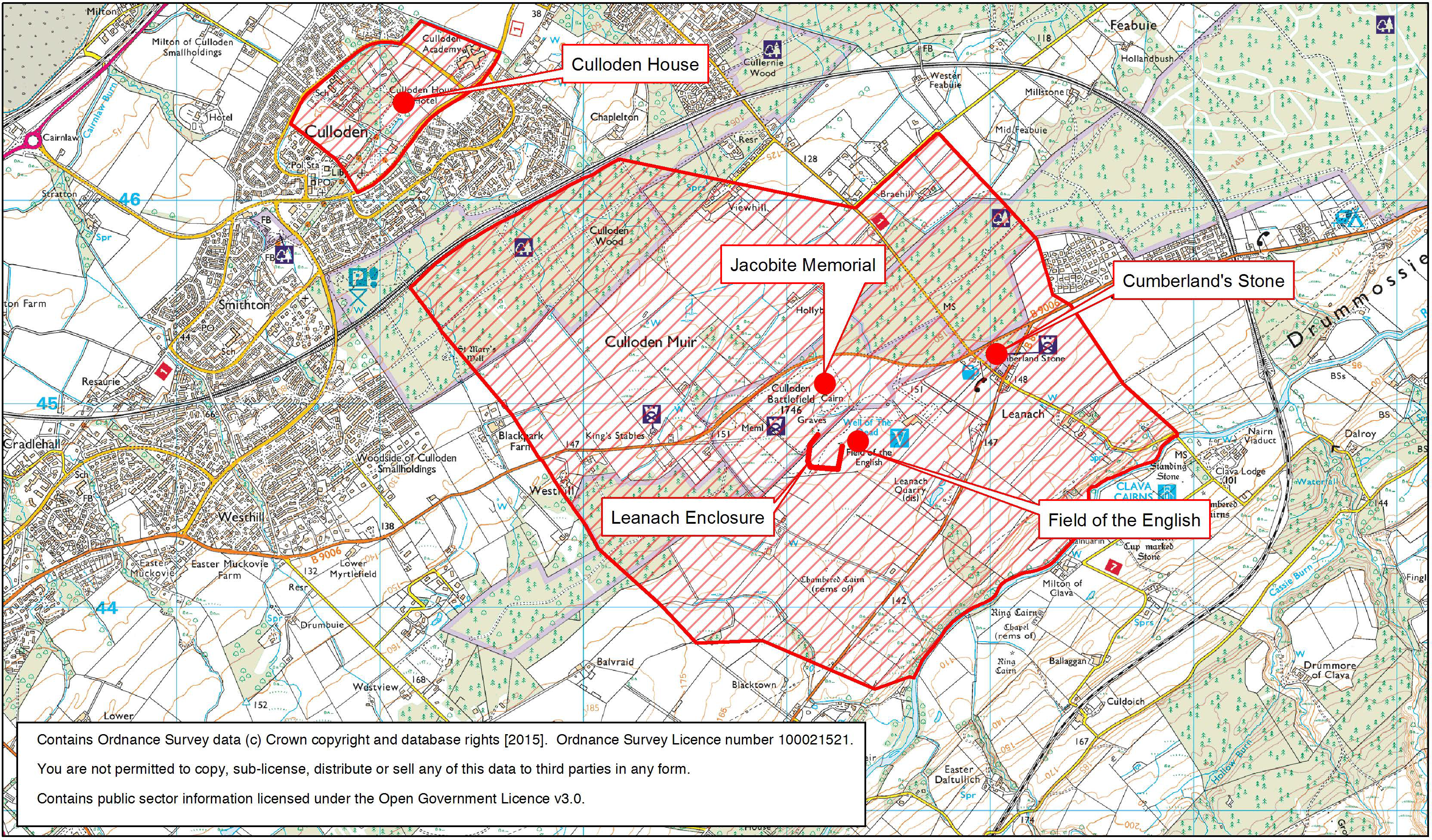

The location of the battle on Drummossie Moor is well established through detailed contemporary maps and archaeological investigations. At the time, the moor was used as rough grazing with some arable but with stone walled enclosures to the north and south. The Jacobites anchored their right and left flanks on these enclosures, with the clan regiments in the front line. The Government army advanced on the Jacobites from their camp at Nairn, around 10 miles to the west.

Although the Jacobites had picked the site of the battle, in a location which blocked the approach to Inverness to the west, it was the Government army which set the scale of the field, coming to a halt around 700 m to the east of the Jacobite line. In doing this they maximised the use of their artillery and the distance over which the Jacobites would have to charge, so creating an extended killing ground for both their artillery and muskets. The first Government line formed not far to the west of a small farmstead (Leanach), with the second line forming just to the east of it, with the farmstead thus being towards the left of the Government lines. Leanach was one of a number of farmsteads scattered across the moor and is the only surviving upstanding example. A farmstead was located within the Culwhiniac enclosure and a sketch map by Yorke shows a building located close to the east-west wall of the enclosure which divided it into two. This building appears on the 1st Edition Ordnance Survey map as Park of Urchal (as a ruin) and is also shown on Roy’s map (1747-55). The much-denuded remains of a building can be identified on the ground at this location. The third farmstead was located to the west of the Culwhiniac enclosure and is no longer extant.

Between the Jacobite right and the Government left sat the turf-built Leanach enclosure. Barrel’s regiment on the far left of the Government line formed across the mouth of this enclosure though some distance to the east of it. The right wing of the Jacobite charge passed through the enclosure, which was probably a denuded feature by the time of the battle. The moor on the northern part of the battlefield, in front of the Jacobite left, was wetter ground than to the south, so much so that the Jacobites charging here were unable to close with the Government right in contrast to the situation on the left where fierce hand-to-hand fighting took place.

The enclosures to the north (Culloden Parks) and south (Culwhiniac) played an important role in the battle as the Jacobite army anchored its left and right flanks respectively upon them. The Government dragoons also passed through breaches made in the walls of the Culwhiniac enclosure, while the Campbells positioned themselves behind its northern wall to deliver fire into the Jacobite flank. The enclosures were demolished in the 1840s but a walkover survey in 2005 identified the possible foundation courses of both, which in the case of the Culwhiniac enclosure corresponded to a modern field boundary.

Other aspects of the Culwhiniac enclosure may also have survived from the time of the battle. For instance, a gate in the eastern side of the modern fence line, which correspond to the line of the earlier wall, appears to represent the point at which the Campbells breached the wall in order to allow passage for the dragoons through the enclosure, as it corresponds with the location of the breach on contemporary maps and written accounts of the event.

Topographic survey across the core of the battlefield area identified subtle undulations in the terrain, which may have served to partially shield the Jacobites on the right and centre, while their absence on the left may explain the failure of Jacobites on that side to close with the enemy during the charge.

The battle was fought on partially open moorland situated on the crest of a broad sandstone ridge which ran from east to west between Nairn and Inverness. The moor is located on gently sloping ground at the base of the Monadhliath mountains. The subtly undulating terrain of the boggy moor which played a key role in the battle is well-preserved and the centre of the battlefield is today occupied by a mosaic of gorse and heather, with pools of standing water and streams giving some impression of the wet conditions that prevailed on the ground at the time of the battle.

Cultural Association

There is little doubt that Culloden is one of the most emotive battles to have been fought in the UK. It is inextricably linked with the romantic image of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Highland Jacobites. The battlefield is one of the most popular heritage tourist destinations in the Highlands of Scotland and has become almost a place of pilgrimage for ex-patriot Scots and other members of the Scottish Diaspora from places such as USA, Canada and Australia, especially those with Highland ancestry.

The greatest focus for modern visitors is undoubtedly the Clan Cemetery. The site continues to be a place of great importance to clan associations and groups such as the White Cockade society. There are, however, popular misconceptions about the battle, among them being that all the Jacobites were Highlanders and that it was a battle between the Scottish and English rather than part of a civil war played out against the backdrop of the pan-European War of Austrian Succession.

The battle has featured prominently in literature, art and other media throughout the passage of time since the battle. The most famous painting of the battle titled ‘An incident in the Rebellion of 1745’ by French artist David Morier was painted soon after the battle and shows the Government and Jacobite troops in close combat. The battle and its aftermath has featured in popular culture through film, such as Michael Caine’s adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1971) and television, such as the groundbreaking 1964 BBC docudrama Culloden, based on the popular book Culloden by John Prebble (1961) and an episode of Doctor Who (1966).

The NTS has owned and maintained parts of the battlefield since 1945. A purpose-built visitor centre was constructed in 1970 and the Trust embarked on a conservation programme which has succeeded in re-routing the road away from the Clan Cemetery and removing areas of forestry. Further land has been purchased to prevent the sale of parts of the battlefield for housing developments and the current aim of the Trust is to return much of the battlefield to its appearance in 1746.